|

|

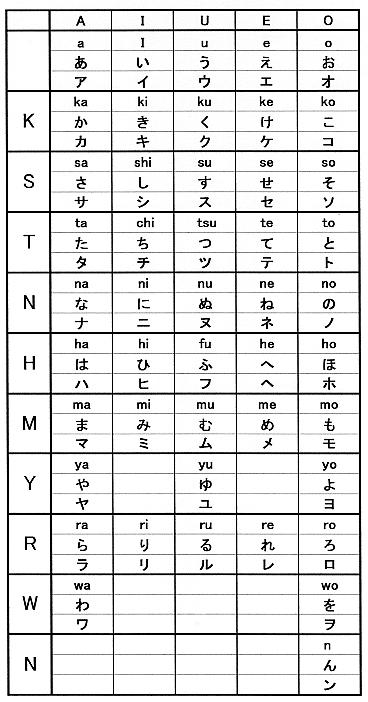

Hints and tips that may help you to understand better..., The impression that the Japanese culture and especially the Japanese language is thousands of years old is so common that it comes as quite a surprise to discover that this impression is not exactly accurate. There is absolutely no indication of any form of written language prior to the introduction of the Chinese characters in the 6th century, A.D. The first books written in Japanese were the NIHON SHOKI (Chronicles of Japan) and the KOJIKI (Records of Ancient Matters), both written in borrowed Chinese characters, called KANJI in Japanese. Since the Chinese and the Japanese languages have basically nothing else in common except the Kanji, the Japanese written language naturally evolved from the Chinese over the centuries to accommodate its own needs by adopting two more forms of writing. These two systems are called HIRAGANA and the KATAKANA, and are collectively known as KANA. Each of the Kana systems has 70 characters that signify a specific sound very much in common to the Latin alphabet. Every Japanese word can be written in Kana, but in general Katakana is used for non-Japanese words while Hiragana is used for native function words, such as verbs, verb endings, and particles. A Japanese writer may also resort to using hiragana when he or she doesn't know or remember a certain kanji. Below is a list of all the Kana:

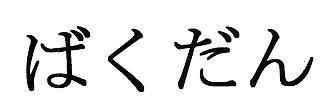

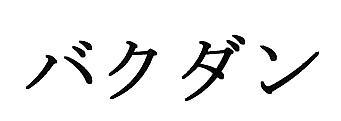

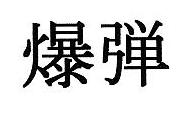

Å@ As mentioned above, the Japanese also use the Kanji, the Chinese characters, of which the Japanese have taken in more than 7,000, over time. No need to panic,however! Just around 2,000 are in common use today in newspapers and books. But many of the characters that interest students of Japanese military and aviation are outside of the limited number in common use. This fact makes some trouble for us who study the language in connection with our aviation interests. What makes the Kanji different from the Kana is the fact that each Kanji represents one "idea", one word. Therefore, they are called "ideograms". The Japanese, since they adopted the Kanji from the Chinese, use either the Chinese pronunciation of the Kanji, called ONYOMI, or their original Japanese pronunciation, called KUNYOMI. Confused? Let's try to simplify things a bit. Let's take for example the word BAKUDAN (bomb). If we want to write the word BAKUDAN in Hiragana, we would first write the character for the sound BA, then KU, then DA and then N. But apart from the Hiragana there are two specific Kanji that mean nothing else but bomb. So if we want to write "bomb" in Japanese we can either write it in Kana or in Kanji, as we are doing here:  - Hiragana, - Hiragana,  - Katakana, - Katakana,

- Kanji - KanjiJapanese use all three systems when they write and while it is fairly easy to memorize the Kana, it's a really a pain to remember the 2,000 Kanji and sometimes their two different pronunciations. So, why don't they just use the Kana? Well, there was some thought given to doing that after WWII, during the Occupation, but it simply didn't work out. The Japanese are happy with their Kanji, just as the Chinese are happy with their symbolic written language, and a recent survey among foreigners living in Japan showed that even they are happy with the Kanji and wouldn't like to see them abandoned. Another question that frequently comes to mind asks if the Chinese and Japanese can understand each other and can communicate with each other. The answer is no. The spoken language is completely different, and the people of the two nations can barely understand some basic words by using the common characters. Disappointed? Well, Japanese students learn Kanji up until high school and there were even more Kanji to learn until the end of WWII. But, as mentioned above, many characters were abandoned and not learned by young Japanese of more recent times, making them less competent in their own language than their grandfathers and their fathers were. Furthermore, Japanese grammar is a piece of cake and the vocabulary is just there to learn. So don't lose heart! Or as the Japanese would say: GANBARE! TIPS 1. Japanese names are traditionally written with the family name preceding the first name. An example is offered here, using the name of the famous naval ace. "Sakai" is the family name; "Saburo" is the first name. We follow this rule everywhere on our site, therefore you will see "Sakai Saburo" here, instead of Saburo Sakai, as is customary in some other writings. 2. Pronunciation. Japanese language pronunciation is fairly difficult for English speakers but not so much for the Italians, Germans, Russians or Greeks, for these are languages that have clear and distinct sounds. Each sound is pronounced clearly, very similar to the Latin/Italian pronunciation. There are no variations of the basic sound, as in English, Korean or Thai. The "A" sound is always "A" (as in "father") and the accent is usually flat. In order to accomplish this flat accent a nice trick is first to try to punctuate strongly and equally each "syllable"/sound/Kana and then drop the volume of the voice and accent. For example, don't say: RIkugun or riKUgun or rikuGUN. But first try to say RI-KU-GUN and then lower your voice. Here is another pronunciation point to remember. Taking another look at the above list of the Kana, we can see that the letters/sounds "V", "L", "HU" (as in "WHO"), "FA", "FI", "FE", "FO", "YI" and "YU" are not included; they don't exist in Japanese. Furthermore 2 or 3 consonant combinations, like "BRother" or "deSTRoyer" (with the exception of the combination with the "letter" "N") and words ending in consonants (with a couple of exceptions) are impossible. Therefore when native Japanese speakers try to pronounce non-Japanese words they often use combinations and alternatives, or they change the words to fit their standards; very often with results that have absolutely no resemblance to the original word. Let's see some examples: "TEBURU" means "table", "DOA" means "door" and (the best) "REDI FASTO" means "Lady's first". Apart from being amusing, the above nonexistent sounds cause great problems to the deciphering of non-Japanese place names, among others, therefore some practicing and imagination is necessary. "BITONAMU," for instance means "Vietnam". We are sure that you can see from this example how difficult it is to interpret such words. Would you have known what "BITONAMU" meant if we hadn't told you? As mentioned above, equally difficult is the pronunciation of Japanese words by English speakers. Let's see a couple of common mistakes in pronunciation and concept: "kaMAkaze". Correct pronunciation is "KAMIKAZE" with the sound "MI" like in "mimic". "Fuji Yama". The highest mountain of Japan is never called like that but always "Fujisan". 3. "SAN", "SAMA", "SENSEI". The common honorific word after the family name for addressing someone regardless of sex, is "SAN". Use it to address everyone older than you, non family members...or in just about every case, except close friends. "SAMA" is the more polite form commonly used to address complete strangers (Example: "DOCHIRA SAMA DESU KA" - "Who is it?") or customers or if you just want to be over-polite. When addressing teachers or doctors Japanese use the word "SENSEI". For sumo wrestlers the word is "SEKI". And while all the above sound straightforward enough, there is a difficulty in the Japanese language that is the cause of much confusion. The problem is how to write Japanese using the Latin alphabet ("Romaji" in Japanese). One major difficulty lies in the variety of vowel pronunciation. There are "pure" vowels, "stretched" vowels and double ones. There are for example words that have a simple, "pure" "o" sound; words with a "stretched" "o" that is shown in Hiragana with the addition of an "U" (in Katakana usually this is shown with an "-") and there are double "o"s in a word. Another lesser difficulty is in the double consonants. In Kana this is shown with a small "tsu" added before the respective "Kana". There are various systems/ways that Japanese can be written in "Romaji" and encounter the above problems. Let's take the word "HIKOKI" which has a "stretched" "O" for example to see the differences in writing. One system is the indigenous Japanese that children learn at elementary school. This system is based on how the words are written, not how they sound, and it must be said that it's highly unfriendly to non-Japanese. In this system our example would be written as "HIKOUKI" but you shouldn't pronounce the "U". In this system the sound "TSU" is written "TU" and the "CHI" as "TI". Another way is by using the Hepburn system. This is largely based on how the words sound and is much more friendly. In this system a macron would be used over the "O" in our example, so it would be: All the above systems are proposals to the problem of writing Japanese using the Latin alphabet trying to be more or less helpful to the student of the Japanese language. None of the above ways is "official" or world wide accepted. Furthermore it should be remembered that the Latin alphabet is used by various peoples speaking a variety of languages, not only English speakers. The way a Spanish speaker or an Italian would write Japanese in Romaji, would be much different from the way an Australian would. Furthermore, the above systems are ways to reproduce the Japanese in Romaji either based on the sound of the word or the way the word is written. None can show how much "stressed" this "O" is (much like in Classic music), they just use an indication that this sound is "stressed". A classic example of the above confusion is the word "TOKYO". Both "O"s are stressed, so Japanese would write "TOUKYOU". What almost nobody notices is that the "KY" is written with an "Y" not with an "I" as would be proper. This is to help English speakers pronounce the word "TO-KE-O" not "TO-KAI-O". This doesn't make much sense or difference to Italians for example. Since all the above are confusing, we will try to simplify things in our site as much as possible. Keeping in mind that this "stretched" sound is much less significant in the written word and to those who want to read (not speak) Japanese, we do not show it in any word in our site. We simply ignore its existence. After all the purpose of this site is not to teach Japanese, much less a perfect Japanese pronunciation. We cannot imagine our visitors to read aloud the contents of our site. The above systems would make sense and be helpful to those who would really be interested in learning Japanese not to modelers or even fans with just a passing interest. So to summarize all the above: 1. "Pure" vowels are left as they are as shown in the Kana table. 2. "Stretched" vowels are ignored. No indication is included unless the only difference between two words in Romaji is this stretched sound. In that case we will mention that it is stretched. 3. Double vowels are shown by simply repeating the same vowel. 4. Double consonants are shown by simply repeating the same consonant. 5. Whenever the "SA", "SU", "SO", "TSU" sounds are pronounced thickly (with a small "YA", "YU", YO" after them), they are written as "SHA", "SHU", "SHO", "CHU". In the next page we have started a simple dictionary with the most frequently encountered military terms in Japanese. If you encounter any different "spell" of the words below, don't be confused. They are not different words. It's because of the above mentioned problem. After this short cultural encounter, let's continue with some commonly encountered military words and phrases. PAGE II |